If ever a career in music was

pre-ordained it is that of Paul Simon, the ambitious, gifted and ever-so-scrupulous

first son of a professional double-bass player and the champion of this book, a

biography as diligently researched and carefully considered as any of the songs in Simon’s extensive

repertoire. Though clearly an admirer of his music, Peter Ames Carlin

nevertheless feels duty bound to cast a less than approving eye on a man whose

self-belief – some might call it arrogance – results in him repeatedly turning

a deaf ear to well-meant advice, often with unfortunate results, as well as a distressing

reluctance to share credits with collaborators. He's also on the depressive side, unfulfilled despite it all, and consequently resorts to psychoanalysis, usually successfully. The result is that Homeward Bound portrays Paul Simon as largely uncongenial, certainly not

someone with whom you’d want to relax over a couple of beers, let alone share a

catchy riff you’d discovered on your own guitar.

On the plus side,

Simon is no fan of the cult of celebrity, generous towards charities and always

pays his musicians well, sometimes when they don’t even know it, as was the

case with British folkie Martin Carthy who introduced him to, and taught him

how to play, ‘Scarborough Fair’, the traditional ballad that opens Parsley Sage Rosemary And Thyme, the third album Simon recorded with

singer Art Garfunkel. Simon credited himself as the writer but dutifully sent a

proportion of the royalties to Carthy’s music publisher who shamefully failed

to pass them on, with the result that in his ignorance Carthy held a grudge against

Simon for years until the issue was finally resolved after they shared a stage

together in 2000.

This is but one of

many interesting instances that Carlin brings to light where Simon appears

guilty of minor larceny. Plagiarism is too strong a word, but Simon has a

tendency to hear something, or be alerted to something, which after a good deal

of chopping and changing, remixing and re-arranging and almost always adding

his own lyric, he makes his own. Often this is tangential, as in the case of

the musician Heidi Berg who in early 1984 drew Simon’s attention to music from

South African townships by famously loaning him a cassette tape she had found

entitled Gumboots: Accordion Jive Hits No

2. Simon liked what he heard and two and half years later released Graceland, heavily influenced by that cassette and which arguably rescued his

career, or at least gave him a new one, but Heidi Berg, without whom, is

mentioned only in the very small print and referred to not by name but as ‘a friend’

in Simon’s own sleeve note. She didn't even get the cassette back.

At the heart of this

book is the volatile relationship between Simon and Garfunkel, a running theme of

friendship and hostility that Carlin returns to time and again, often with

eye-opening revelations about their endless rivalry and petty squabbles. This

began in the Tom & Jerry era, that rather odd pre-S&G phase wherein

they launched themselves as a precocious doo-wop duo, all smiles, crew cuts and

sweaters, a time of innocence you might think but you’d be wrong. To his credit

Carlin has researched this period, about which little has been written before,

with extraordinary diligence, so much so that I found it one of the strongest

parts of his book (vying with the political fallout from Graceland and the slow-burn build up to the Capeman debacle). Accordingly, we learn

that Jerry (Paul) went behind Tom’s back, making recordings of his own under

various pseudonyms, and that when Art found out he went ballistic. Even now,

over 55 years and heaven knows how many millions of records sold later, this

subterfuge still rankles. Its nadir was probably reached when they refused to

be photographed together for a 1981 hits compilation, thus requiring their

record company to hire lookalikes photographed in shaded soft focus as they

stroll by gentle waves along a seashore.

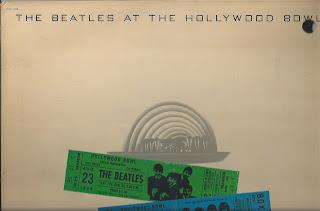

Simon & Garfunkel, or is it?

All of this keeps us

on tenterhooks as we progress through the sixties, the S&G years. They keep

up the pretence well, the best of friends as their renown escalates, amiable quips shared on stage, but the

tense undercurrent is always there, exacerbated by Simon’s need for control,

Garfunkel keeping him waiting, their physical differences and the overlying sense that

their personalities simply don’t gel. Well, John and Paul Beatle didn’t always

see eye to eye either and neither do Mick and Keith Rolling Stone, let alone the Everly,

Davies and Gallagher brothers, so perhaps we have disparity to thank for some

of the finest pop music of the second half of the 20th Century, and

I include in that the three greatest S&G albums, Parsley…, Bookends and Bridge Over Troubled

Water.

Long before the

break-up of S&G it is clear that Simon wants to make it on his own, and it

is also clear that he has always had eclectic tastes, that never ending need to

broaden his musical palette. He was researching ‘world’ music long before Graceland; witness ‘El Condor Pasa’ on

the Bridge album, ‘Mother And Child Reunion’ on his first solo

record and the gospel and Dixieland excursions on his second, … Rhymin’ Simon. He is an avid reader of good books, a confidant of A-list actors, TV directors and film makers, and he repeatedly

reaches out to teachers who can offer knowledge of technique, musical theory

and literary skills. As a result, the career lows – notably the One Trick Pony movie and Capeman musical – tend to be redeemed by

the quality of the songs within, both lyric and melody, which Carlin

analyses and critiques with a clear eye for style, detail and procedure. It is to Simon’s

credit that when things do go awry for him he has an uncanny ability to back

off, lick his wounds and bounce back, even if that does mean a call to his old

friend and rival who lives in equal splendour to himself on the other side of New

York’s Central Park.

The book is

refreshingly direct, focusing almost exclusively on Simon and only very

occasionally veering off into matters concerning his rivals, usually Bob Dylan,

or politics, and only then when it is pertinent to career choices that the

generally apolitical Simon makes. Too many rock biographies resort to this kind

of thing as padding but this one doesn’t, and to this end Simon’s personal life

is not ignored. We learn of his marriages, and how the first two – to Peggy

Harper (the ex-wife of S&G’s manager) and to actor/writer Carrie Fisher –

broke up, and his immediate family, a troubled only son from his first marriage, and three later children, two boys and a girl, with third wife Edie Brickell.

We learn too about the earlier generations of the Simon lineage, the tailor

from Galicia, another Paul, who emigrated to America in 1903, and Louis the bass

player, who found it difficult to come to terms with his son’s fame and enormous fortune. He desperately wanted his elder son to become a teacher and it wasn't

until this very famous son reached the age of 50 that Louis could finally find the words to tell the multi-millionaire rock star, his boy who drew 750,000 to a concert in Central Park, how proud he was of his

achievements.

Finally, I warmed to

his book because here and there Carlin drops lyrics from the Simon canon into

his text, usually to stress a point yet never tritely or as a cliché. Search

and ye shall find. It’s a lovely touch, a sure sign that not only does Peter

Ames Carlin know his subject inside out but that he cares about his readership.

Those fans that might be deterred by the unflinchingly objective light that Homeward Bound shines on Paul Simon will nonetheless be charmed by the

warmth bestowed in this pleasing, slightly whimsical, attention to detail.

Highly recommended.