About 45 minutes into this gaudy, fast-paced, acclamatory biopic of Elvis, the camera focuses in on its hero sat on a folding chair at an upright piano. He’s in the corner of a large room, illuminated from behind by light shining in from two windows, playing and humming a gospel melody, a reflective moment amid the madness that is going on around him. In fact, the scene is a direct, and deliberate, reproduction of a still photograph taken by Alfred Wertheimer during rehearsals for the Steve Allen TV show in New York on July 1, 1956, and represents an almost fanatical fixation on the part of this film’s producers to depict small details accurately.

Perhaps the producers felt this dogged adherence to the precise truth was necessary to mitigate against a handful of glaring inaccuracies inserted to dramatize, and at times rather overegg, the plot, the most absurd of which is the suggestion that Elvis would have gone to jail on a trumped-up charge of behaving lewdly in public had he not answered the call of Uncle Sam and joined the US army in 1958. Allied to this, and unmentioned in any of the many Elvis books I’ve read, and therefore probably fictitious, is that Parker was threatened with deportation over his alien status by right-leaning politicians unless he somehow prevented Elvis from moving on stage in ways that sent teenage girls delirious but profoundly displeased their God-fearing parents.

Elsewhere I doubt Parker signed up Elvis for his very first Vegas season to pay off gambling debts – though this may have occurred later – or that Elvis fired him from the stage of the Hilton International, and if Priscilla arranged for Elvis to go into rehab, she didn’t bother to mention it in Elvis And Me, her best-selling memoir.

These wildly contrasting aspects of the screenplay aside, I enjoyed every minute of a two hour and 20-minute film that never lagged. While at heart a potted biography, the recurring, all-important side-plot hinges on Elvis’ relationship with the scheming, Machiavellian Parker who managed him throughout his career, taking 50% of his client’s earnings, and probably more. Parker cleverly manoeuvres himself into Elvis’ life, persuading the naïve singer and his equally naïve parents that he is indispensable, his best friend, when in reality he is Elvis’ worst enemy, at least as far as artistic growth and financial remuneration are concerned. Tom Hanks makes a great villain in his portrayal of the dislikeable Parker, overweight, lumbering, ugly and speaking with a nasty quasi-Boer accent born of his Dutch ancestry, of which Elvis was forever ignorant.

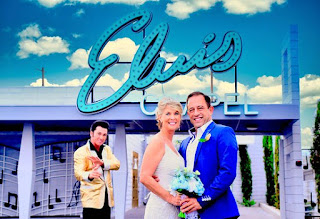

Austin Butler makes a convincing Elvis, the only Elvis impersonator I have seen who mimics both the vital, pre-Army Elvis and the jump-suited Las Vegas showman in both his pomp and decline. Most of the set pieces of Elvis on stage are fantastic, seriously exciting, very loud too, most notably the lengthy screen time devoted to the ‘Singer’ special, and because the film is authorised by the estate we hear and see the real Elvis from time to time, as well as Butler splendidly imitating his stage gyrations and singing voice.

Supporting actors Olivia DeJonge, as Priscilla, Dacre Montgomery as Steve Binder, the producer of the ‘Singer’ special, and Luke Bracey as Jerry Schilling, the only member of Elvis’ entourage who encourages Elvis to defy Parker, are all impressive, their various roles in the story true to life. The same applies to Richard Roxburgh as Vernon, Elvis’ spineless father.

There are a few omissions or, at least, areas of Elvis’ life that are skimmed over unduly quickly. There’s not much about his movie career; indeed, the schlock film era, the period between his leaving the army in 1960 and rediscovering his mojo in 1968, goes by in a flash. A veil is drawn over Priscilla’s age – 14 – when she met Elvis in Germany, as well as her and Elvis’ subsequent romantic relationships. Elvis’ promiscuity and drug use are touched on, along with his temper tantrums that caused TV sets to become targets for his impressive arsenal of firearms.

The vexed question of why Elvis never toured outside of the United States is raised to a significant degree, the answer of course Parker’s inability to travel because he didn’t have a US passport, and couldn’t apply for one without incriminating himself. His claim that it was for security reasons is soundly derided. Parker’s unwillingness to allow Elvis to venture outside of a tried and tested formula, his undermining of Elvis’ more radical ambitions, is a constant theme, as is Parker’s greed, his unshakable belief that Elvis remained little more than a goose that laid golden eggs.

The film closes with the real Elvis singing ‘Unchained Melody’ at a concert two months before his death. Although I’ve seen this heart-stopping performance many times on YouTube, I’d never seen this footage – or heard Elvis’ still remarkable voice – in the clarity it is presented here. Overweight, sweating, visibly trembling as he plays a grand piano, he gives it his all, an absolutely extraordinary display by one of the greatest singers of all time. It was the perfect ending to a very watchable film.