I wasn’t entirely sure what John Lennon meant when he sent me a postcard on January 28, 1977, telling me he was ‘invisible’ but it became pretty clear soon enough. In the years that followed he was invisible to the rock world, wiling away his days on an extended break from music and all the promotional chores that releasing records entailed. The only other musician of John’s stature to have taken a similar step back is David Bowie, ironically also during the last decade of his life, a career decision that might have been promoted by John’s absenteeism.

Only a select few people knew precisely what John was up to: Yoko, of course, and their infant son Sean; staff at their homes in New York’s Dakota apartment building and elsewhere; a few people from his past, among them the other three Beatles, the odd musician and, probably, son Julian from his first marriage; and a handful others that John bumped into in the course of his wanderings.

John was all too well aware that the contradiction between the enormous fame he attained as the boss Beatle and the lower-than-low profile he maintained from 1976 onwards would attract intrusive press speculation but, by and large he succeeded in his quest to become invisible. His whereabouts and doings between 1976 and 1980 were shrouded in relative secrecy at the time and only became public knowledge in a sort of drip-by-drip fashion, mostly from interviews undertaken immediately before his assassination in December 1980 and biographical or memoir-style books published thereafter. Now, all that information has been assembled into this one volume, somewhat misleadingly titled since the first half of the book liberally strays into the half-dozen or so years before 1980.

What we learn is that John’s relationship with Yoko had its ups and downs, and they spent time apart, albeit remaining faithful in the bedroom department after the 1973-4 separation. Such separations, although temporary, invariably caused John anguish, especially if for some reason he was unable to reach Yoko by phone. Yoko took care of business, buying cows and houses, often basing her decisions on numerical or astronomical charts, leaving John to take up the role of hands-on father to Sean, perhaps to make up for paying scant attention to Julian’s upbringing when he was distracted by Beatle business.

He stayed home a lot, read books, magazines and newspapers and watched TV, following the news avidly. He picked up a guitar every now and again to write a snatch of a tune, often recording these bits and pieces on cassette and hoarding them until such a time when he opted to release music again. He was largely graceful to fans who encountered him on his wanderings in the New York Westside neighbourhood where he lived, even to those who somehow eluded the Dakota’s security system, but the most important thing is that he was agreeably content, relaxed, unburdened by any contractual obligations, free to do precisely what he wanted, even learn to bake bread.

With his green card secured, he was able to travel outside of the US without fear of being refused re-entry, and such travels are covered here in extraordinary detail, thanks no doubt to the author’s interviews with Fred Seaman, the Lennon’s PA, whose 1991 book The Last Days Of John Lennon covered much the same ground. John flew to Japan with Yoko, and, alone, to South Africa for no good reason than a need to observe the Table Mountain at close quarters. He also piloted a yacht to Bermuda in challenging weather conditions, the perilous nature of the voyage suggesting we were lucky not to have lost John to the Black Hole of Andros close to Bermuda, the journey’s destination. This adventure reflects his wilful, slightly eccentric character, the odd leaps and bounds he took when no one, not even Yoko, was looking. Such escapades endear him to me almost as much as his music.

As the years rolled by, however, the need to make music was uppermost in his mind and second half of the book, largely devoted to 1980, faithfully records numerous sessions under the production aegis of Jack Douglas at the Hit Factory studio in New York. We learn in tremendous detail how the songs that mainly comprised the Double Fantasy album were written and recorded and who played on them, which is not quite as interesting as John’s peripatetic habits in the first half, though there are tantalising particulars of tentative plans he was making for a world tour in 1981. Finally, I was pleased the author avoided all mention of John’s assassin and any gory details of the appalling crime he committed.

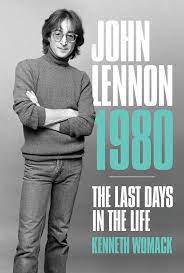

Still, for a detailed account of John’s final days this book is unrivalled. In the picture on the cover, taken by Jack Mitchell on November 2, 1980, during an assignment for The New York Times, bespectacled John, his smile assured, his arms folded, looks to me rather like a left-leaning lecturer on sociology at a red-brick university in the north of England. Among the photos inside is a map of the Dakota’s interiors, as well as a few other pictures from the lost half-decade I hadn’t seen before. There are copious source notes, a comprehensive bibliography but the books lacks an index.

No comments:

Post a Comment