Back in 1993, charged with compiling tracks for what became 30 Years Of Maximum R&B, The Who’s 4-CD box set, I was offered (and eagerly accepted) a live version of ‘Bargain’, recorded at this show. In an essay for Crawdaddy magazine shortly after the set was released in 1995, I wrote that ‘Bargain’ was the best reflection of The Who at their finest on the whole box set. “This is a truly stupendous performance, fluent, confident, full of highs, a perfect example of The Who at the peak of their ability, reckless yet somehow still in control, flowing with their music, relishing their skills.”

This version of ‘Bargain’ had already been made available on MCA’s Who’s Missing, released in 1985, while two other songs performed at this concert, John’s ‘My Wife’ and Don Nix’s ‘Goin’ Down’, a spontaneous closing jam, appeared on Two’s Missing a couple of years later. I ought to have pressed for more from the show for 30 Years, just as I pressed for a whole live Tommy as a fifth CD, but I had a hunch there was a covert strategy to hold back material so that it might be used on future re-issues at some unspecified date. Then again, it might be that the estate of Bill Graham, whose BG Productions promoted the Civic Arena shows, had tried to claim ownership of the recordings, as they had with other concerts, and this issue needed to be settled before the entire concert could be released.

Whatever the ins and outs of the matter, it has now been made available on two CDs among the ten included in the Who’s Next 50th Anniversary super-deluxe box set, just released by Polydor and costing a whopping £224.99 on The Who’s own website, with slight price variations elsewhere.

The Who’s 25-day American tour at the end of 1971 holds special memories for me as I was present at the opening date, at Charlotte, North Carolina, on November 20, on what was my first ever visit to the USA, and I have written about this elsewhere on this blog. The two concerts in San Francisco on December 12 and 13 followed 15 others across the South and West Coast of America, with the tour concluding on December 15 in Seattle. I am reliably informed that contrary to what it might state elsewhere, the show on the two discs in the bells and whistles Who’s Next is from the 13th and not the 12th; also that the live ‘Bargain’ on 30 Years was from the 13th, and not from the 12th, as stated in the track listing.

But all this is academic. What really matters is that The Who were on the form of their lives that December, the greatest rock band in the world performing the greatest music they ever made, a combination of brilliant songs from Who’s Next and Tommy sprinkled with bits of their past and a hint of the future. They were also cresting a wave of Stateside popularity, so a massive anticipatory ovation greets Bill Graham as he introduces the group in typically sonorous tones, like a Master of Ceremonies announcing distinguished guests at a VIP banquet, pausing for effect between each name: “Four of the greats and four very nice people,” he says. “On bass, Mister John Entwistle, … on vocals, Mister Roger Daltrey, … on drums, Mister Keith Moon (which, inevitably, prompts a flourish around the kit), … on guitar, the king, Mister Peter Townshend. The Who.”

Within seconds the staccato chords of ‘I Can’t Explain’ ring out loud and clear, like a hammer on an anvil, and they’re off, electrifying their fans as only The Who could in those days. Roger sounds angry on an angry song; John’s lines complement Pete’s chords; Keith sounds like an automatic rifle on the chorus. ‘Substitute’ follows, tight and snappy, and somehow even better, the combined vocal attack in perfect sync. All four are on top form tonight and know it. Roger introduces ‘Summertime Blues’, a belter, as ever, similar to Leeds except Pete solos mainly above the 12th fret, high frequency, and ‘My Wife’, “by our bass player, affectionately known as The Ox”, which explodes after the second verse, Roger repeatedly yelling “Keep on moving” and “Oh, she’s coming” as Pete solos and Keith goes manic. After another verse this whole eruption is repeated, only this time they step back to idle for a moment, clearly improvising, enjoying the moment, then tumble back in for another bout of sheer pandemonium. It is a portent of things to come. At just over six minutes ‘My Wife’ is the longest work out so far. Prolonged cheers ensue.

“Here’s a song [for] which we use a tape to put a synthesiser sound on stage,” announces Roger. “It was a lot easier than getting someone to play it. We couldn’t handle that, getting someone else. Anyway, Pete plays the synthesiser on the tape so it’s just like playing with two Petes if you like. [In the background, you can just hear Keith yelling, ‘One’s enough!’] It’s a great song. I really like this one. The lead track off Who’s Next, ‘Baba O’Riley’.”

By my reckoning this is the first live version of this Who staple, as performed by them, ever officially released and there’s a freshness to it here not found elsewhere, especially in Roger’s vocals and the moment when Pete urges us not to cry as it’s “only teenage wasteland”. The crunch chords sound like bells and the accelerating harp coda last just over a minute before arriving at a sudden, unexpected, well-drilled stop. Perfect.

It’s Pete turn to talk. “No sooner have we taken you up than we’re gonna take you down again, very slowly,” he says. “This is a cameo, if you like, of a Who performance. It starts off nice and easy and ends up sort of bouncing all over the stage. We start off without Keith Moon and end up with him.”

This is the cue for some horseplay from the drummer, the light-hearted repartee that so often took the edge off Pete’s intensity, furnishing The Who with a skittish sense of humour rarely found in rock groups of their stature. “All right then I’ll piss off,” we can hear Keith muttering.

“I wasn’t trying to get rid of you or anything,” retorts Pete.

“It’s been nice working with you,” adds Keith, acting pissed off. “I’ll see you later.”

“It’s called ‘Behind Blue Eyes’,” says Pete before telling the audience that the set for tonight has been changed, presumably from the previous night. Knowing full well that Who fans would be attending both nights, he seems to delight in second-guessing them. Perhaps inspired by Moon’s quips, he adds: “It’s special but it’s all rehearsed, you know. We work out these dance steps, me and Roger, for hours.”

There follows one of the loveliest versions of one of The Who’s loveliest songs I’ve ever heard. As in ‘Baba’, Roger is pitch perfect, moving effortlessly from the purity of the verses to the tough middle section and back again. Pete’s hammering on and off during the arpeggios is clean as a whistle and when Keith re-joins the group their focus is pin sharp.

And so, we come to ‘Bargain’, “a song about what you get from being here,” says Pete. “If you’re alive, whether you’re rich or you’re poor, if you’re up or you’re down. If you’re alive, you’re getting a bargain.”

I wrote about this performance of ‘Bargain’ at length in my essay for Crawdaddy, and I can’t improve on it, so here we go again. During the opening chords Pete gleefully shouts something off mike which is difficult to make out, but it sounds like a call to arms that simply enhances the anticipation. Roger leaps in over Pete’s rumbling guitar before the song’s real highlight, the emotional contrast between Roger and Pete’s separate vocal lines. I especially love the way Pete’s keening vocal refrain is counterbalanced by John’s lovely bass melody and how Pete yells ‘pick me up’ at the top of his voice after his final line. Keith and John take up the challenge in a thrilling bass and drum rumble that launches Pete into a magnificent solo. The song itself, like many that Pete was writing at the time (including – most notably – the climax to Tommy), is a prayer of yearning in which the singer prostrates himself before the blessed one – ”I’d pay any price just to get you,” sings Roger – while in his refrain Pete admits his inadequacy: “I know I am nothing without you”. In some ways it’s possible to mistake ‘Bargain’ for a love song, but when you get your head around the idea that it really is a hymn (to Meher Baba, Pete’s spiritual guru), then it becomes all the more impressive. Then there’s that extended coda, one of The Who’s on-stage trademarks, in which the song appears to be over until Pete launches into a series of fragile chords before finding his way into another riff, taking the others if not by surprise then at least by the lead as he pounds on, carried along by the momentum, confident that the band are on such good form at this moment that it would be a crime to stop just because the song is at an end. Quite wonderful. Then there’s another roar from the crowd.

Up and down. Dark and light. Earnest and comic. “If you were here last night you will have noticed my knees trick,” says Pete as the cheers die down. “If you’re wondering why I’ve got such funny shaped knees it’s because I’m wearing knee pads, so I don’t agitate the fractured knee cap.”

“Have it off,” yells Keith. “Amputate.”

Next up is ‘Won’t Get Fooled Again’, mid-set in 1971, again as fresh as you can imagine, sharp and precise, another triumph for Roger, the ensemble playing along with the synthesiser track faultless, Keith an almighty presence both before and after the synth interlude. Roger’s roar at the climax is leonine. In a review of the deluxe Who’s Next in Mojo, Mark Blake wrote of this reading of ‘WGFA’ that it “sounds like The Who achieving the transcendental lift-off that Townshend claimed they managed on a good night, and also suggests drummer Keith Moon might spontaneously combust.” He’s not wrong.

More humour. Pete tells us his Doc Marten shoes have bouncy soles. “High jumpers should wear these,” he adds. “What are we doing now? This one is an old tune we used to do when we very first started, and it would be very nice to think there was at least one person here who saw us in London at the Marquee Club and maybe heard us play this number. We played a lot of Tamla Motown stuff in those days. It was very hip, trendy to play Tamla Motown. We used to play ‘Heatwave’, ‘Dancing In The Street’ and this one. Roger will tell you what it is while I change my guitar. I have to use a special Tamla Motown type guitar.”

“For a change,” says Roger, “we actually feature Mister Keith Moon.” This is the cue for a bit more silliness until Keith charges into ‘Baby Don’t You Do It’, a fierce work-out on the Tamla song recorded by Marvin Gaye, highlighted by Keith’s energetic drumming throughout, Roger’s strident vocals and The Who’s unique ability to turn soul into furious rock at the drop of a hat. Playing off one another as no other band can, there’s some lovely bass work from John, and Pete’s buzz-saw guitar solo towards the end is terrific. During a furious ‘head for home’ climax Pete, John and Keith play their hearts out with Roger hollering to be heard above the din. Then, just to stress the point, there’s a false ending and the band rev up yet again, only for Roger to have the last word. An edit of this recording would become the B-side of ‘Join Together’ the following year.

“Let’s have an English song now,” yells Pete as Roger blows his harmonica. “We’re gonna sell you something. We’re gonna sell you a bus… a magic bus. You’re gonna have to pay us… but it’s worth it.” Keith taps the blocks, John thumps away on one note, playing his bass like a drum, and Pete gives us what Charles Shaar Murray once described as a masterclass in rhythm guitar. At 17 minutes ‘Magic Bus’ is far and away the longest individual song of the night, retaining its tense Bo Diddley tempo and the preposterous horse-trading banter between Roger and Pete until the ten-minute mark when Keith switches to his kit and all hell breaks loose. Then, just when you think it’s all over, it’s not. A false ending is followed by another coda: Roger back on the harp, accompanied only by Keith’s rolls with Pete improvising more lyrics, all building to another breath-taking extended finish.

After all that most bands would be taking a bow and heading for the dressing room, perhaps returning after two minutes for an encore. Not The Who. It’s time for Tommy. Professor Keith Moon is introduced as the conductor. “Daltrey, stop drinking on stage,” he yells. “John, stand still you ruffian.”

“He’s breathing,” says Pete.

Keith: “I’ve told him not to move on stage.”

Pete: “Actually I’ve seen him moving in hotel rooms.”

Keith: “He gets up to turn the television on and off.”

Pete: “He picks the phone up. Room service…”

Keith: “Hot tuna sandwich.”

After a count in from Keith – “three million, four million” – The Who launch into the ‘Overture’ from Tommy, played with its usual panache, followed by Pete’s unaccompanied solo guitar piece, much of it improvised, leading into the intro to ‘Amazing Journey’. This is followed by the instrumental ‘Sparks’ on which, for the first and only time, the guitar mix seems too low, at least for the first two or three passes until the octave drops sweep in. A minute later it’s all back on balance, and the three instrumentalists are up and away, sailing head-on into the ‘Underture’ storm with Keith leading the charge for a full four minutes. The audience erupt at the end.

After a breather ‘Pinball’ arrives, Pete’s furious strumming punctuated by John’s stabbing bass, another hell-for-leather ride leading to ‘See Me Feel Me’, the spiralling Tommy hymn which, as ever, raises the roof as The Who pay tribute to their audience, climbing mountains and seeing the glory, a truly majestic performance.

But it’s not over yet. “It feels good to see you standing up,” says Pete. “This one is where we drive you back into your seats again. ‘My Generation’ – are you in it?”

And off they go yet again, into their biggest, most sacred hit, a faster version that on record, Roger screaming the lyrics, John rattling off the bass solo, Pete finding a riff in his solo, then another, then another while everyone follows him into unchartered territory until John and Keith cotton on to where he’s going and gamely follow while Roger sings whatever comes into his head. After eight minutes it settles and Pete works his way into the nagging riff of ‘Naked Eye’ which Roger sings beautifully, the other three straining at the leash until, as in so many other songs tonight, the structure breaks open to allow more free-form soloing which this time morphs into the bluesy ‘Going Down’, after which the concert finally ends. The combined length of ‘My Generation’, ‘Naked Eye’ and ‘Going Down’, all segued together, is almost 24 minutes, this on top of the 90 minutes plus beforehand. It goes without saying that the final climax is explosive, electrifying. I have no idea how long the cheering continued as only a minute can be heard on this recording. There would have been no encore.

* * *

Sometimes, just occasionally, even though there’s pictures of them as young men on the walls of my home, I forget how great The Who once were; when they were young and pioneering, forever moving forward, lighting a path that no other group of their era could tread. For my money, The Who in 1971 left every other group on the planet in their wake. For a few glorious years they were simply untouchable, playing out of their skulls night after night, the greatest rock concerts ever. I’m not that enamoured of the recent activities of Pete and Roger, though I don’t blame them for carrying the torch, playing their music in whatever form they choose to present it these days for those that still want to hear it played on stage. They are musicians and that’s what musicians do. I’m just not that interested any more.

What I am still interested in, however, and still delirious about, are Who recordings like this 1971 San Francisco Civic Auditorium concert, just as I was over the Moon about that 1968 New York Fillmore show. My review of that, by the way, has had almost 50,000 hits, far and away the most of any posts on Just Backdated. So, I’m not alone in feeling this way.

It’s been fun writing again about The Who I loved so much.

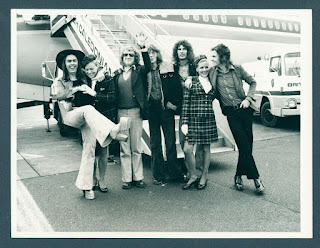

(The photo at the top of this post was taken by Jim Marshall at the San Francisco concert on December 12, 1971.)