I never felt closer to The Who, my all-time favourite group, than I did in New York during second week of June, 1974, and this includes the periods, between 1993 and 2000, when I worked on and off for them on their box set and back catalogue reissues. A ‘them and us’ relationship between the music press and the top groups of the day emerged with the arrival of punk in the UK, but it never affected my relationship with The Who. I tried to maintain my neutrality with them but I admired them so much, both as a group and as individuals, that becoming close to them was somehow important to me and, of course, it helped me get the hot Who scoops for Melody Maker.

On June 10 The Who opened an unprecedented four-concert run at Madison Square Garden, shows that sold out on the strength of one radio announcement, all 80,000 seats. No other act had played the Garden four times in one week before and to say I was anticipating these shows eagerly would be an understatement. I was at every one, either in a good seat or at the side of the stage, and in their dressing room.

It therefore pained me to report that The Who weren’t at their best in New York this time around. Equipment glitches were partly to blame but an exacerbating factor was a fan down at the front on the opening night who yelled “Jump Pete, jump” to Townshend, which shocked him enormously. For the first time, he said later, he felt he was parodying himself, even resembling a circus act. Furthermore, he found he needed to force his uniquely athletic stage style, which had previously come naturally to him and was so much a part of the excitement of The Who’s stage shows.

In the short term this contributed to an unsatisfactory run of concerts, at least by the absurdly high standards The Who had set in the past. In the long term, what he experienced at the Garden had a profound effect on his attitude towards the group. Most fans loved them regardless, of course, and their blind faith depressed Pete still further.

From where I was sat on the first night I couldn’t see the fans up front but I could tell something wasn’t right. I put it down to sound problems, as was so often the case when they hadn’t played for a while. The Who were like elite athletes who needed regular training to obtain optimum results. When they took on a lengthy tour the first few shows might have been slightly under par but when they hit their stride, Olympic fitness as it were, they were supreme, untouchable. When they played the odd show here and there, as they did in 1974, they suffered through being out of condition – and sometimes it showed.

This was the first time they’d played the Garden so the acoustics were new to them. I thought they’d iron out the problems after the first night but they didn’t, not really. It was only later that I realised the real problem ran far deeper, and I suspect that the band used the dodgy sound as an excuse when they, or at least Pete, knew the problems lay deeper too. They hadn’t recorded any new material since the previous year’s Quadrophenia, so the set they played was a run-through of their past, a kind of greatest hits selection. The only real surprise was that for the first time since the Tommy era they re-introduced ‘Tattoo’ into the set which the fans (and I) loved but which somehow contributed to a slightly unsettling feeling of nostalgia that had hit me earlier when I saw High Numbers t-shirts on sale outside the Garden. Pete always wanted to progress but the others were content with the way things were, and this was also part of the problem. It was a problem that would never go away, not while Keith was alive anyway.

“A huge roar greeted the arrival of The Who and the first half hour of Monday’s show was quite electric,” I wrote in MM. “But from then on it slid into a murky mess of badly mixed sound, flared tempers and general untogetherness. Things went wrong from ‘Behind Blue Eyes’ onwards. Daltrey had difficulty pitching the ‘See Me, Feel Me’ lines and at one stage he kicked over a monitor speaker in a fit of rage. Townshend could be seen shouting at the sound men and the taped synthesiser backing tracks were too loud. Towards the end the sound did improve but by this time it was too late to count. Townshend even apologised but it didn’t seem to matter. They still got a standing ovation, but it was a hollow victory for the band.”

The backstage passes at the Garden were these four 'face' badges, one for each night.

I still have mine.

My friend Pete Rudge, who handled The Who’s US affairs in those days, had given me passes for all four nights and backstage I overheard a terrible row after this opening concert. The Who were screaming at each other behind a locked dressing room door. Their co-manager Kit Lambert, who wasn’t often seen at Who concerts by 1974, had turned up unexpectedly, drunk as a lord, and was demanding to mix the on-stage PA the following night, a ludicrous suggestion that exacerbated an already fraught situation. Long serving soundman Bobby Pridden ran out of the dressing room shouting that he was through with The Who, and I took him aside into another room and spent about 20 minutes beseeching him not to quit, and of course he didn’t. Poor loyal Bob, the real fifth member of The Who. He caught it in the neck so many times but he loved them far too much to ever quit.

Eventually things calmed down and Rudge asked me to do everyone a favour by quietly steering Lambert away from the scene which I somehow managed to do. On our way back uptown to the Navarro Hotel I asked Kit if he could ask his limousine driver to stop so I could buy a pack of cigarettes. We stopped and Kit rushed into a liquor store and came back with two cartons of Marlboro for me – 20 packets!

The concerts improved as the week went by but The Who never really fired on all four cylinders that week. Tuesday was much better than Monday, though, and after this show I took Pete, John and Keith downtown to Club 82 where Television were playing. Pete had mentioned to me that he wanted to see some young New York bands, and I thought Television’s spiky, unsettling minimalism might be his cup of tea. He liked them but John, ever the traditionalist, hated them. I don’t know what Keith thought as he disappeared once we got inside the club, no doubt in search of female company. I don’t think he realised that Club 82 was a drag club that often featured female impersonators and ran by lesbians who dressed as men.

Wednesday was a night off and I did an interview with Pete in his hotel room during the afternoon. He seemed in a bad way, stressed out through working on the Tommy film soundtrack, drinking too much brandy and torn between the wishes of the fans, the band and what he wanted to do himself. I think he felt a great responsibility to everyone: the other three, the fans, the film producers and, of course, his young family. Everybody wanted a piece of him, even me interviewing him for MM, but he needed a break from everything. It was telling that when I knocked on his hotel room door he took a long time to answer. I might even have woken him up, and I’m pretty sure he was hung over.

“We were acting,” Pete told me as we discussed whatever it was that afflicted the group on the opening night. “We’ve been able to act and look as if everything’s OK for a while now but we can’t keep it up if the sound doesn’t get better. It didn’t and we couldn’t act for the whole show.”

He seemed grimly aware of the expectations of his audience. “These fans feel that they own The Who. They were there in the front row at the Murray the K Shows [in 1967] and now that The Who have reached this stage they feel that as they’ve been so loyal they have a prior claim to what numbers we’re going to play and things like that. New York to us is like what the Goldhawk Club is like to us in England.

“Most of these kids, the ones I’ve met, seem to have a similar attitude to life. The ones you saw freaking out at the front are the fanatics and they all seem to be deeply intellectual people who are very worried about life. They find The Who to be a kind of gut release which is what I get from The Who, too. They’re people from the dead suburbia of New York who need a release from everyday life.

“The trouble with all of us in this group is that we have such incredibly defined traditional ways of playing that we tend to be bogged down by them in some senses, but I like to go out and do a solo on single notes instead of the usual routine.

“Without becoming alarmist about it I guess that I don’t get as much out of performing on the stage as I used to. I don’t have the same lust for gut feedback that I used to and more and more I want to get feedback from pure music.

“I think The Who are going to have to allow themselves time to breathe without allowing their sense of identity to dissipate. I don’t want The Who to end up on stage playing because they have to but playing because they want to. If it turns out they don’t want to play together, then I don’t think they should, but at the moment we don’t play that often and when we do it’s because we want to. I can’t wait to get back on stage tonight.”

During their stay in New York, Pete stayed in a different hotel – The Sherry Netherland – to the rest of the band who took suites at the Navarro on Central Park South which over the years had become the band’s regular New York berth. It was the first time that the whole group hadn’t stayed together in the same hotel, which I thought was revealing, but Pete stayed in touch with developments at the Navarro by using a rudimentary cordless mobile phone, probably one of the earliest of its type, that had been assembled by the group’s sound crew.

At Thursday’s show ‘My Generation’ morphed into Van Morrison’s ‘Gloria’, a rather disjointed stab at The Kinks’ ‘You Really Got Me’, sung by John, and ended with ‘Big Boss Man’, a Jimmy Reed blues staple from their early days. It seemed to me they were loosening up, finding a semblance of form at last, but try as they might the shows somehow never reached the peaks of the touring that followed the release of Who’s Next, or the closing shows on the Quadrophenia tour for that matter.

After that show Keith, his assistant Dougal Butler and I visited John Lennon at the luxurious Pierre Hotel, where he was living with May Pang. The Pierre was a swanky hotel on Fifth Avenue at the south east corner of Central Park and Keith, Dougal and myself rode there in a limousine from the Garden, then headed up to John’s suite in the elevator. John seemed pleased to see Keith. They’d been pals back in London in the sixties and had been hanging out together in LA earlier in the year. In truth, Keith was a Beatles groupie, eternally in awe of them, and also a good pal of Ringo whose son Zak – who now drums with the 21st Century Who – was the recipient of at least one Moon cast-off drum kit.

Keith, being Keith, suggested to John that we all have a drink, assuming, wrongly as it turned out, that John would have a huge bar stocked with booze. In the event, all he had was one bottle of extremely expensive red wine, a fine vintage red, given to him by former Beatles’ manager Allen Klein. John said he thought the bottle cost $1,000 but was a bit spooked by this and mentioned that he was, at present, involved in a lawsuit with Klein who might therefore have good reason to poison him. John suggested that someone in our company should taste the wine before everyone else took a drink.

Looking around he said something like, “Well Keith, you can’t taste it because you’re the drummer with The Who so you can’t die, and you need your assistant Dougal. I’m John Lennon, the famous Beatle, and I can’t die either. May Pang is my companion at the moment and I don’t want her to die, therefore the only one of us left to taste the wine is you Chris... so here you are.”

The bottle was duly opened, John poured some wine into my glass and I sampled it as the others all stared at me. There was a moment’s silence while they waited to see whether I would keel over on the spot, and I was half tempted to clutch my throat and make a gargling sound – but to this day, that was the finest glass of wine I’ve ever drank in my entire life, so rich, full-bodied, bursting with flavour. “It’s absolutely beautiful,” I said. It was duly shared out, but once the wine had gone Keith was eager to move on, so we left.

As we were waiting for the elevator Keith decided he wanted to take a pee but was reluctant to return to John’s suite and disturb him. So he peed down the Pierre Hotel laundry shaft instead.

On Friday, the final night of The Who’s week of shows at the Garden, Pete smashed three of his Gibson Les Pauls and Keith joined in, chucking his drum kit everywhere and smashing the fourth and only remaining guitar. I was told that Bob Pridden had taken delivery of around a dozen Les Pauls from Mannie’s, the music shop on West 48th Street, and would return the unused ones at the end of the week.

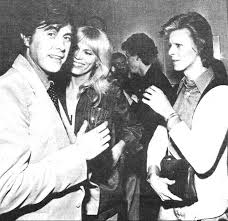

My date at this final concert was Debbie Harry, and we sat together on John’s side, a few rows up from the stage. No doubt keenly aware how Chris Stein had saved up for his guitars, she was appalled by the destruction. Backstage in the dressing room after the show Roger tried to put the make on her – “Fuckin’ ‘ell Chris, that bird looks just like fuckin’ Marilyn Monroe” – as did Keith, equally unsubtly. She didn’t respond to either of their advances, I’m happy to report, which didn’t please Roger whose strike rate in this department was always very high.

Debbie H & CC at the after-show party.

Note the 'John' backstage pass badge on her lapel.

Debbie spent the rest of the evening with me, taking in an after-show party at a roller-dome where we danced a lot and Bob Gruen, ever on my trail, took more photographs, including several of us together. It was a lavish affair where 1,500 guests, among them Elton and assorted Beach Boys, were entertained by Ronnie Spector & The Ronettes.

The Who wouldn’t perform again for 15 months.