Over the years I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve been asked how I got my job on Melody Maker. The simple answer is that I answered an ad in the back of the paper and went for an interview but there was much more to it than that, a culmination of events and circumstances rather than some long-held ambition of mine to join the staff of a music paper. Nevertheless, before I switched to MM, at the height of Beatlemania I can recall buying New Musical Express to read about The Beatles and thinking that their reporter, Chris Hutchins, must have a great life, but it didn’t occur to me to try to follow in his footsteps, not yet at least.

These events and circumstances began slowly during 1968 but accelerated rapidly during the second half of 1969 and into 1970. Some came about through coincidence, some through my own actions and some through the actions of others, but I’m getting ahead of myself here and before recalling the decisive step I made in early 1969 I need to mention a chance encounter with the real music world that occurred during the late summer of the previous year.

Towards the end of August I took my fortnight’s holiday from the Bradford newspaper to spend one week in London, then drive down to Devon for a second week, staying near Salcombe where the friend who accompanied me knew someone with access to boats. Before we went chasing mackerel in the Kingsbridge Estuary, however, we had an errand to run in London, to observe a group rehearsing and report back to a Yorkshireman who’d invested in them. John Roberts, who lived in Settle, north of Skipton, was a wealthy paper manufacturer considerably older than us who took a keen interest in jazz and rock. He’d invested £500 – about £9,000 in today’s money – in a group formed by Jon Anderson who before he travelled south had sang with The Warriors, a band from Accrington that John Roberts had befriended.

The group, of course, was Yes. My friend and I watched them rehearse in a basement beneath the Lucky Horseshoe restaurant on Shaftesbury Avenue where, as friends of their investor, Jon welcomed us and introduced us to the other members. The music we heard was a far cry than what I was used to playing in my covers bands in Yorkshire, very complex and skilful, and the songs seemed to go on for far longer than I’d encountered before, but it was all very professional and when we returned to Yorkshire we were able to report back to John Roberts that his money was probably safe.

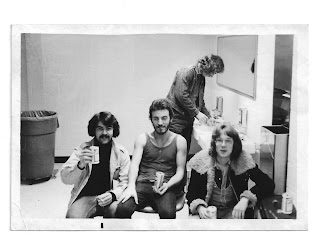

Yes in 1968; photo by Barrie Wentzell, whom I would encounter on MM

In London we stayed in a B&B on Sussex Gardens and used John Roberts’ introduction to gain entry to La Chasse Club on Wardour Street, a watering hole for the music industry. We were, of course, on the prowl for girls but our attempts at chatting up fell on stony ground with young women who preferred the company of long haired musicians to country bumpkins like us. Still, this was all very exciting, my first brush with the pop world, a far cry from magistrates courts and councils, and it made an indelible impression on me.

I went back to Yorkshire, wrote more for The Swing Section in the T&A and was even persuaded by the editor to go undercover to report, not particularly successfully, on the use of illegal drugs in Bradford’s pubs and clubs. Then, early in 1969 the younger members of the staff on the paper were informed that its owner, Westminster Press, was launching a new evening newspaper in Slough and that anyone who wanted to work on it would be given relocation expenses and a pay rise. The first edition would be published on May 1.

My shock horror expose of drug use in Bradford

Three of us from the T&A took up the offer, on my part because I fancied living away from home though I didn’t necessarily want to move away from my parents. There was no one incident that heralded a dramatic departure but I was feeling stifled and needed a change, and Slough was close to London where live music was plentiful. My mum didn’t want me to go and on the day I left, a sunny Easter Sunday, she became teary, as did I. But I was 22, old enough to make a break.

For a month I lived above a pub on Eton High Street, watching the snotty schoolboys in their drape jackets and starched white collars who in a better world wouldn’t rule over us when they came of age. Then I found a flat in Slough above a hairdressing salon on Farnham Road, sharing with two girls, one a reporter from the paper, the other our lovely editorial secretary whose ambition was to become one. As soon as I was settled I drove up to Yorkshire to retrieve my records and brown Dansette auto-change.

The first edition of the Slough Evening Mail

The work was much the same as it was in Bradford, courts, councils and committees, but there were two established weekly newspapers covering the same beat, the Slough Observer and Windsor & Eton Express, and their reporters didn’t appreciate us muscling in on their territory. There wasn’t any overt unpleasantness, just a sense that we weren’t really welcome. Also, aside from a massive upturn in my sex life – I was soon sharing my bed with the editorial secretary, whom I’ll refer to as JJ – I didn’t much like Slough. The circulation area took in Windsor and Maidenhead, both lovely Thameside towns, but Slough itself was a dump, epitomised by the Trading Estate across the road from our flat. Also, there wasn’t much opportunity for writing about music and no one on the paper’s hierarchy seemed inclined to remedy this.

One weekend that summer I took my new girlfriend JJ up to Yorkshire and showed her the Dales. My mum was in hospital at the time with a recurrent back problem but JJ met my dad and Skipton friends of mine whose beer consumption noticeably alarmed her. Born and bred a southerner, JJ was a bit of a fish out of water in Skipton, admired for her looks but still an offcumden, as many of my pals called anyone born south of Sheffield. I don’t think she enjoyed the experience.

Meanwhile, although I’d always been a Beatles and Stones man, another group was creeping up on me and in May they gave us Tommy. I’d admired The Who since I first saw them in 1965 on Ready Steady Go! and I’d already bought a few of their singles and the LPs Sell Out and Direct Hits, but this new LP, with its gatefold sleeve and dreamlike artwork, was something else again. To JJ’s mortification I played it endlessly on the Dansette. Among other things, Tommy told me I needed a proper stereo.

After the first flush of romance with JJ, the honeymoon period, I began to realise I’d leapt into a comfy domestic situation without really thinking, from one extreme to the other after the relative celibacy of living at home. JJ didn’t share my enthusiasm for rock music and I was quietly relieved when she was offered a job in journalism on a paper in Harrow, which enabled us to drift gently apart. I left the place we’d shared and went to live at Englefield Green, near Egham, in a mansion in its own grounds that had been converted into funky flats. Here I shared space with a photographer, a draughtsman who worked on a Taylor Woodrow building site and a Jack-The-Lad travelling salesman who played the drums and somehow juggled two girlfriends, each ignorant of the other.

Forest Court, the converted mansion where I lived in Englefield Green.

This photo was taken by me in 2018.

The biggest story I covered on the Slough Evening Mail was when a gang of Hells Angels and their women occupied an empty mansion at Bray, close to the M4 near Maidenhead. Neighbours alerted the police after partying had gone on for a couple of days and there was a stand-off between the bikers and the cops that went badly, the issue resolved only after reinforcements were called. The Angels ended up in court at Maidenhead where their mates filled the public gallery after a parade around the town’s one-way system on their choppers, dozens of them, a real show of force, the whole pageant observed by a large crowd of nervous onlookers. I reported on it all and thought it was great fun, not an opinion shared by the magistrates who sentenced the ringleaders to jail terms. Much to my surprise, I discovered that Eton, of all places, was a hotbed of Angel activity.

When I wasn’t working, usually covering much the same stories and events as I’d done for five years now, I was playing records and scheming. I went into London and bought myself a new guitar, a Gretsch, and a Dynatron stereo, two speakers at last. Each week I read Melody Maker. I befriended a guy who turned me on to Led Zeppelin and The Doors. I smoked my first joint. I went to a party in London where The Beatles’ White Album was playing and was given some acid, not realising until too late. I still don’t know how I drove home.

Gradually, the vague haze of delirium was creeping up on me.