Asked by me in 1970 to name his favourite guitarist, Ritchie Blackmore didn’t hesitate. “Albert Lee,” he replied. Pressed further Ritchie, never the humblest of men – “I can play the ass off most guitarists around today,” he once told me – admitted that Lee, Hendrix and Jim Sullivan, who’d given him lessons in the fifties when they lived in the same street in Hounslow, were the only UK guitarists he considered to be superior to himself.

I ought to have known about Albert Lee but I didn’t, not then. I was new to Melody Maker in 1970 and while I knew all the guitarists in the spotlight – Clapton, Beck, Page, Townshend and the like – I wasn’t familiar with Albert Lee. So, I made enquiries and discovered that at the time he played in a band called Head Hands & Feet that was signed to Island. A call to their PR, my friend David Sandison, and their LP arrived on my desk at MM. It contained Albert’s signature song ‘Country Boy’ and after I’d played it a few times I realised what Ritchie was on about.

I saw Head Hands & Feet three times in the next couple of years, supporting Mott The Hoople at the Albert Hall in July 1971, and in the final paragraph of a review devoted almost entirely to Mott, wrote: “Head, Hands & Feet opened the show, spotlighting Albert Lee’s guitar mastery to the full. His country sounding solo on ‘Country Boy’ was one of the best guitar solos I have heard in a long time.”

Now a fan, further exposure to Albert occurred at the Weeley Festival near Clacton-on-Sea that same year and at the Lincoln Festival a year later. Each time my attention was glued to the guitarist.

He was a skinny little guy with a big grin and a mop of dark curly hair that looked like it had never seen a comb. He bent over his butterscotch Telecaster and played like an American, like the session cowboys of Nashville or his hero James Burton. His solos were dazzling, his licks phenomenal, his runs as quick as lightning, his fingering as accurate as a pocket calculator. He seemed modest too, for while he played like a demon he was never showy, never one to ‘make it cry or sing’, as Mark Knopfler put it, never one to screw up his eyes as if in agony or otherwise invite his audience to look at him and him only. He was restrained when someone else was soloing, content to strum chords and fade back into the rhythm section, and it seemed to me that he shrugged off his skills as if it was nothing, really nothing, just what he did, that’s all. He was what was known in the trade as a musicians’ musician, secure in his skills, a master craftsman.

I wanted to meet Albert but never got the chance, not until 1976 when I was doing a story for MM on Emmylou Harris. She was performing at a club on Long Island near New York where I lived at the time and in the afternoon of the show I interviewed her in the dining room of the hotel where she was staying with her Hot Band, their newest recruit Albert. Seems he was asked to replace Burton who’d gone off to play in Elvis’ band, so he was following in the footsteps of his idol, hot on his tail in fact.

I learned from her that Albert hadn’t even rehearsed with her band before their first show together. “It came to a stage where we needed a firm commitment from James (Burton) but an Elvis tour came up right at the time we needed him to do some dates with us, so we needed a new guitar player real fast,” Emmylou told me.

It was Emory Gordy, the Hot Band’s bass player – he’d seen Albert playing with a latter day line-up of The Crickets – who introduced Lee to the fold. “He came down to see us at a place in San Bernardino and joined in to play every song,” said Emmylou. “He didn’t miss a lick all night.”

The Hot Band were sat at an adjacent table, polishing off a very late breakfast. Emmylou beckoned Albert over to join us and I shook hands with him for the first time. “I was supposed to go along to two or three gigs and watch James playing, but actually I’d listened to the records so I knew most of the things they were playing anyway,” he said, with the calm ease someone who knows his business.

“I’d been living in California for about a year after having worked with Joe Cocker but that had finished so I was looking for a new gig. I was asked to go down to some gigs and if I’d like to do it and I knew even before I saw the band that I would love to. Actually, James got the flu so I was rushed into the band faster than I expected. I went down to a gig to watch and thought I’d bring my guitar just in case. I ended up playing all night.”

“Someday this band is going to have a rehearsal,” added Emmylou. “Just to see what it’s like.”

Over the next few years, Albert befriended James Burton – the two can be seen playing together on YouTube – and joined Eric Clapton’s stage band but the next time I saw him was at Abbey Road Studios in 1981. He was there with Chas (Hodges) & Dave (Peacock), both veterans of the UK rock scene from which Albert emerged as a guitarist in the sixties with, among others, Neil Christian & The Crusaders and Chris Farlowe & The Thunderbirds. Chas & Dave were recording a live album in Studio One which had been refitted as a pub for the night and they’d asked Albert along to beef things up. Hodges had played bass in HH&F and both he and Peacock appeared on Albert’s first solo LP, Hiding, released in 1979.

I chatted with Albert that night, and over a pint or two between sets asked him a bit about his long career. I used this information for his entry in my book A-Z Of Rock Guitarists, in which I recognised his dilemma, writing: “If ever there was a British guitarist who deserved fame and fortune in equal doses, it is Albert Lee. Shy, non-pushy and often indecisive, he has remained in the background while his peers have reaped the rewards that fate has bestowed on them. Without a doubt he is the finest country and western picker in the UK and his feel for the blues can rival Clapton. The truism that it takes more than talent to become a rock star is amply demonstrated in Lee’s case.”

Two years later Albert was on stage at the Royal Albert Hall with The Everly Brothers for their comeback concert, not only as their lead guitarist but as their musical director, not that you’d know it from the Ev’s Reunion Concert CD I have in my collection. None of the backing band – among them pianist Pete Wingfield – are credited in the flimsy liner notes, though Don does introduce them from the stage. As ever Albert’s guitar work is exemplary, mostly fills that replicate run for run the well-known Every Brothers’ recordings, though he takes a stinging blues solo on Jimmy Reed’s ‘Baby What You Want Me To Do’ (titled, oddly ‘Blues [Stay Away From Me’] on this CD), and stretches out on the rock’n’roll 12-bars that close the show.

The last time I saw Albert was in June 2012 at a Guitar Master Class in Guildford promoted by Anderton’s, the city’s guitar store. To an audience I judged was 99% guitarists and 1% my wife, Albert, his hair now white, talked about his career, answered questions and, of course, dazzled everyone with a few songs, interspersed with immaculate solos, played on a Music Man guitar with whom he had a sponsorship deal. During the questions, someone asked him why he resigned from Eric Clapton’s band. He played the chug-a-lug riff from ‘Lay Down Sally’ and asked: “Would you want to play that every night?”

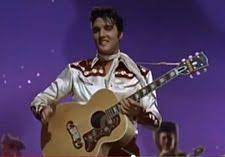

A more poignant moment occurred when Albert, who nowadays lives in Los Angeles, talked about being shown around the Paramount Film Studios and finding himself in a storeroom that housed old props. “In there was the guitar that Elvis played in Loving You,” he said. “A lovely Gibson J200 acoustic, blonde. I picked it up but it was in terrible conditions. Its strings were rusty, its neck was warped. No one had cared for it. It was Elvis’ guitar. I wanted to weep.”