“He didn’t have personal friends,” says Dick Allen, a showbiz agent who worked with Chuck Berry for years. “I travelled all the time with him. We were not socially friendly. He did his thing and I did mine. I did not try to crawl into his life. I have nothing bad to say about him on a personal level; we were just not personally friendly. But he wasn’t personally friendly with anybody.”

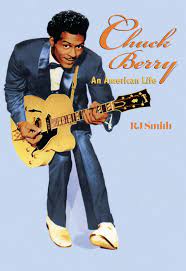

Dick Allen’s testimony is echoed throughout RJ Smith’s engrossing biography of this most secretive of men, the nearest thing we are likely to get to a definitive portrait of a musician whose records are a key foundation stone of rock’n’roll. Berry was elusive, moderately affable when it suited him but more often immensely dislikable, an individualist who never felt the need to bare his soul to anyone, not even his wife Themetta, to whom he was married for 68 years and who gave birth to his three daughters and one son, none of whom are mentioned in the acknowledgements of a book the author proudly states is ‘unauthorised’.

From the book we learn what made Berry the way he was, ill-tempered and arrogant, a provocateur who never gave anything away, least of all what he felt was his due in hard cash. When he died in 2017, aged 90, he had outlived almost all of his contemporaries but enough of those who encountered him remain for Smith to have researched an extraordinary life as diligently as anyone could hope. It’s full of the stories you would expect, mind-boggling tales of meanness and avarice, sexual escapades that border on perversion, and haughtiness that implies an almost suicidal tendency to provoke, and to hell with the consequences.

Were it not for his frequently abhorrent sexual behaviour, Berry might be judged to have taken a heroic stand against racism. He was raised in St Louis, Missouri, and although he had homes elsewhere in the US at one time or another, he never really left. He encountered white privilege everywhere he looked and determined from an early age to behave like a privileged white man himself, especially when it came to his addiction to white women, especially blondes. This got him into lots of trouble but he took it in his stride. His bullishness was who he was.

With the notable exception of his first jail term, ten years (commuted to three) for his part in a bungled crime spree just after he turned 18, there isn’t much about his childhood, the pre-rock’n’roll years, though we do learn he admired the poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar and was fascinated by cameras. As a result, the first 150 pages or so (out of 400+) of the book devote as much time to scene setting as they do to the man himself. Which is not to say that the scene setting isn’t important or, indeed, absorbing, just that biographical details take second place to the history of American blues and R&B music, the gangster-ridden early US pop record industry, Berry's varied influences and, perhaps most important, the ugly racism in America during the fifties, how it impacted on Berry and how he reacted to it.

Smith has a free-wheeling American style of writing that rocks along like a Chuck Berry song, and he likes sentences without verbs. This suits the subject matter if not the subject, who was always laconic in interviews and, like many present day politicians, made things up or massaged the facts, not least in his own autobiography, first published in 1987. Unlike that book, An American Life is generous with the precise details on how, in 1960, Berry was given another prison sentence, this time three years for transporting a 14-year-old native American girl over state lines for sex, not to mention numerous other legal actions brought by women who sued him on sexual grounds, right up to the hidden cameras used to film women using the bathrooms in Berry Park, the country club he established in Wentzville, Missouri.

It therefore comes as a bit of a relief when Smith turns his attention to the music – which he writes about well – and how it was made, and how Berry came to learn about, and then react to, the ways the profits from it were shared. We learn about Johnnie Johnson’s role in the process and Smith has interviewed numerous musicians, some long-serving, from bands hired to back Berry up on the road. All have great tales to tell. Indeed, the last third of book contains countless eye-opening accounts of Berry’s ‘difficult’ behaviour while touring, wrangles over money in which Berry invariably comes out on top, his role in promoter Richard Nader’s endless series of rock’n’roll revival shows and the behind-the-scenes shenanigans surrounding the 1987 film documentary Hail! Hail! Rock’n’Roll, in which Keith Richards suffered for his prominent role.

In the end, though, while Smith is generous in his endorsement of Berry’s musical accomplishments, the portrait he paints is of a solitary, self-destructive, morose and hyper-sexual satyr. For all the pleasure that Chuck Berry’s music has given us, he didn’t get – or even seem to want – much pleasure in return.

Published in the UK by Omnibus Press and elsewhere by Hachette, Chuck Berry: An American Life is well annotated and indexed, has a rather meagre 16 pages of black and white photographs and costs £20.00.

No comments:

Post a Comment