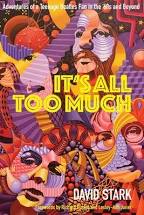

Rock shows at Carnegie Hall were a bit of a rarity during my stint as Melody Maker's man in New York. I can recall seeing The Chieftains there and being somewhat alarmed to see Irish independence sympathisers outside collecting openly on behalf of the IRA. “Spare some change for the old country,” they exhorted, so I kept my mouth shut. But there was an element of prestige involved in playing the Carnegie and Greg Allman pulled out all the stops at his show there in late March. Alongside him on stage were 29 other musicians, with a backdrop and scenery designed to suggest that he’d brought ‘Maykin, Jawjar’ – and he called his home town – to the Big Apple.

The show was produced by Shep Gordon, Alice Cooper’s manager, who never did things by halves and brought a touch of grandeur to the proceedings. My only complaint was that the effort necessary in presenting Greg in this way caused the show to start almost an hour late. Although the now legendary group took their name from Gregg’s surname, he was not the front man when I last saw The Allman Brothers, at the LA Forum the previous year. Guitarist Richard Betts was the star of that show while Gregg hid behind a Hammond to stage left, shyly taking an occasional bow and content to be out of the limelight.

For the solo show, all this was changed. The Hammond stood in the centre of the stage, decked out with flowers and lit candles. The show was clearly aimed at pushing Greg forward, thus working against his natural shyness, and as a result he looked uncomfortable amid the splendour of the smart-suited orchestral back-up men.

In effect we were seeing half of The Allman Brothers Band. There was Chuck Leavell – now The Rolling Stones’ keyboard player of choice – in a straw hat playing a grand piano at stage left, and Jai Johnny Johanssen alternating between bongos and a regular kit. The rhythm section was Cowboy, a quartet of session players from the Capricorn Studio in Macon, and the rest were strings, brass and backing singers with comedian Martin Mull bringing the complement up to 30 by acting as MC.

The concert opened with an orchestral piece played by Leavell at the piano. As the strings and brass came on stronger, the rhythm section joined in and Allman made his entry to the delight of the crowd and chagrin of the stern Carnegie Hall staff who were kept busy returning fans to their seats throughout the entire show.

“Dressed in denims and looking his usual dishevelled self, Allman appeared somewhat out of place,” I wrote. “His long blonde hair covered his features and even though the spotlight shone firmly down on him, he still managed to hide away behind his instrument for most of the time. He sways on the stool so much one imagines that any moment he’s likely to slip off on to the floor. It never actually happens though.”

Predictably, the set comprised material from his 1973 solo album, which was aptly titled Laid Back, and Gregg’s contributions to the Allman Brothers’ song catalogue.

“With such a huge band, the music sounded not unlike Joe Coker’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen band,” I continued. “It was all very well-rehearsed, but Allman’s voice was frequently drowned out by the force of everything else. He doesn’t have the strongest of voices, but when it does shine through, he sings with a loping, casual Southern accent, slurring words together, sounding rather like a mean gun slinger.

“During the entire show, he picked up the guitar only once – to sing ‘Midnight Rider’. This was a shame. He’s as good a guitar picker as you’ll find anywhere, and I’d have preferred to hear him on either the acoustic or electric instrument instead of endlessly pumping away on the organ. He’s a competent, if not brilliant organist but he was given few opportunities to solo and when he did it was nothing too spectacular.”

Oddly, the second half of the show featured Cowboy on their own, with Allman returning for the finale, the massed congregation offering ‘Shine On Your Lovelight’. For an encore Greg played a new, unaccompanied piece at the piano before one and all joined in again for ‘Will The Circle Be Unbroken’.

A day or two later I interviewed Todd Rundgren at the offices of Bearsville, his record label, on East 55th Street, and for reasons best known to himself he brought along his main squeeze, the model Bebe Buell. Perhaps it was to show her off. Ms Buell, of course, was strikingly beautiful and in the fulness of time her name would be linked with Mick Jagger, Jimmy Page, David Bowie, Elvis Costello and Steve Tyler, with whom she had a daughter, the actor Liv Tyler.

Although Rundgren dressed outlandishly onstage and gave the impression that he was ‘way out there’, in reality he was a sober, clear-headed chap who adopted a methodical attitude towards his calling as a musician and record producer. Indeed, he had worked it out so that his successful career in the studio making records for others financed his critically acclaimed but less remunerative career as an artist in his own right.

“I discovered that I didn’t like most of the people involved in the so-called music business, so the fewer people I had to meet the better,” he told me matter of factly. “I figured a producer didn’t need to meet too many people. I like people better nowadays but it’s still not right, so I continue to disinvolve myself as much as possible from the business aspect.”

Most recently Rundgren had been brought in to produce Grand Funk Railroad, and he certainly added some much needed sparkle to this rather dull HM trio. The resulting album, We’re An American Band, compared favourably with all their former efforts and as an added bonus there was a number one single from the title track – something Grand Funk had never had before – and also a modicum of critical acclaim, also new to GF.

“I would say now that Grand Funk are better musicians than the world believe,” said Todd. “It is possible to make a band sound worse than they are in the studio which may have happened with Grand Funk. That’s very easy to do, much easier than it is to make a band sound good.”

We talked a bit about his own band and he was modest enough to admit that though he considered his live performances far more important than his albums, he loses money going out on the road. “I rack up tour debts though and that’s where the money that I make from producing goes. Everything evens itself out in the end.”

I would experience Grand Funk Railroad for myself a few days later, at Madison Square Garden on April 23. I was dumfounded by the volume at which they played.

“Ringing ears are a symptom of excessive listening to loud rock and roll,” I wrote in MM, opening myself up to a charge of stating the bleeding obvious. “When the ears tingle after a gig, you know the band in question has pushed out plenty of juice. When they’re still ringing the following day, then that band must have employed a brave sound engineer to control the volume setting. When the ringing’s still there as you head for bed the following evening, it’s something else entirely. I’ve experienced those ringing ears the following morning, but only once have I known it to last the entire day and into the night.

“That was last Tuesday. On Monday evening I experienced a two-hour concert by Grand Funk, who, regardless of what the Guinness Book Of Records says about Deep Purple, go down in my book as the loudest band I’ve ever heard and, hopefully, the loudest band I’m ever likely to hear.”

I was sat near the front, a mistake though I wasn’t to know this beforehand. In any case, review tickets were almost always ‘good seats’, a description that, in this case, was certainly moot. Still, after all the atrocious reviews I’d read, they were better than I expected, though much of their attraction lay in the effects they laid on: their state-of-the-art lighting rig, the movies shown on a screen behind them and, of course, that terrifying volume.

“Their reception at New York’s Madison Square Garden on Monday evening was nothing short of unreal,” I wrote. “From the opening note, 20,000 fans stood on their chairs and cheered wildly until it was over. The ovation surpassed anything I’ve seen in the States, including Dylan at the same venue, and the enthusiasm knocked current scream-idols flat.

“One young lady, for example, rushed at guitarist Mark Farner from her pitch at the front of the stage. She was roughly hauled aside by a member of the road crew and left to find her own way back to her rightful place at the front of the crowd. Somehow or other she managed to claw her way through the throng to the front again. Not satisfied with her earlier attempt, she dashed the stage yet again to clutch at Farner. Again, the same girl was bundled off. At the end of the show she was back up front again, having somehow pushed and shoved her way back to pole position beneath the sprightly lead guitarist.”

Oddly, towards the end of the show the band deserted the stage while a short film about themselves was shown. Designed to depict the four members of the group in their natural environment, one was seen riding a horse, another on a motor cycle, another in a fast car and the fourth water skiing. Back at my flat later that evening, unable to sleep due to the ringing in my ears, I imagined how it would look if my pals The Who adopted something similar during their concerts: Pete worshipping at the feet of his guru Meher Baba, Roger ploughing his fields, John chasing spiders and Keith hurling a heavy object through a window. Nah - it’d never work.

The following morning, my ears still painfully aware of the previous night’s experience, I breakfasted with the group at their Manhattan hotel, the St Regis. They were all thoroughly likeable guys, though none were particularly talkative, least of all Farner, the leader on stage if not off. Though he’s a bona-fide rock superstar, his conversation was on ration. Drummer Don Brewer was more talkative, while keyboard player Craig Frost, the newcomer, sat back to let the others do the talking. Bassist Mel Schacher was still in bed, suffering from ‘flu.

We talked about the group’s early days as Terry Knight & The Pack, losing Knight – who had exerted a disproportionate influence on them – and how Todd Rundgren had brought about a resurgence in their fortunes. A photographer commissioned by them turned up to take some photographs, including one of me lighting a cigarette (above), sat opposite Mark Farner who can seen in the mirror.